World Social Protection Report 2024–2026

Universal social protection for climate action and a just transition

Chapter 2. From climate crisis to a just transition: The role of social protection

Key messages

-

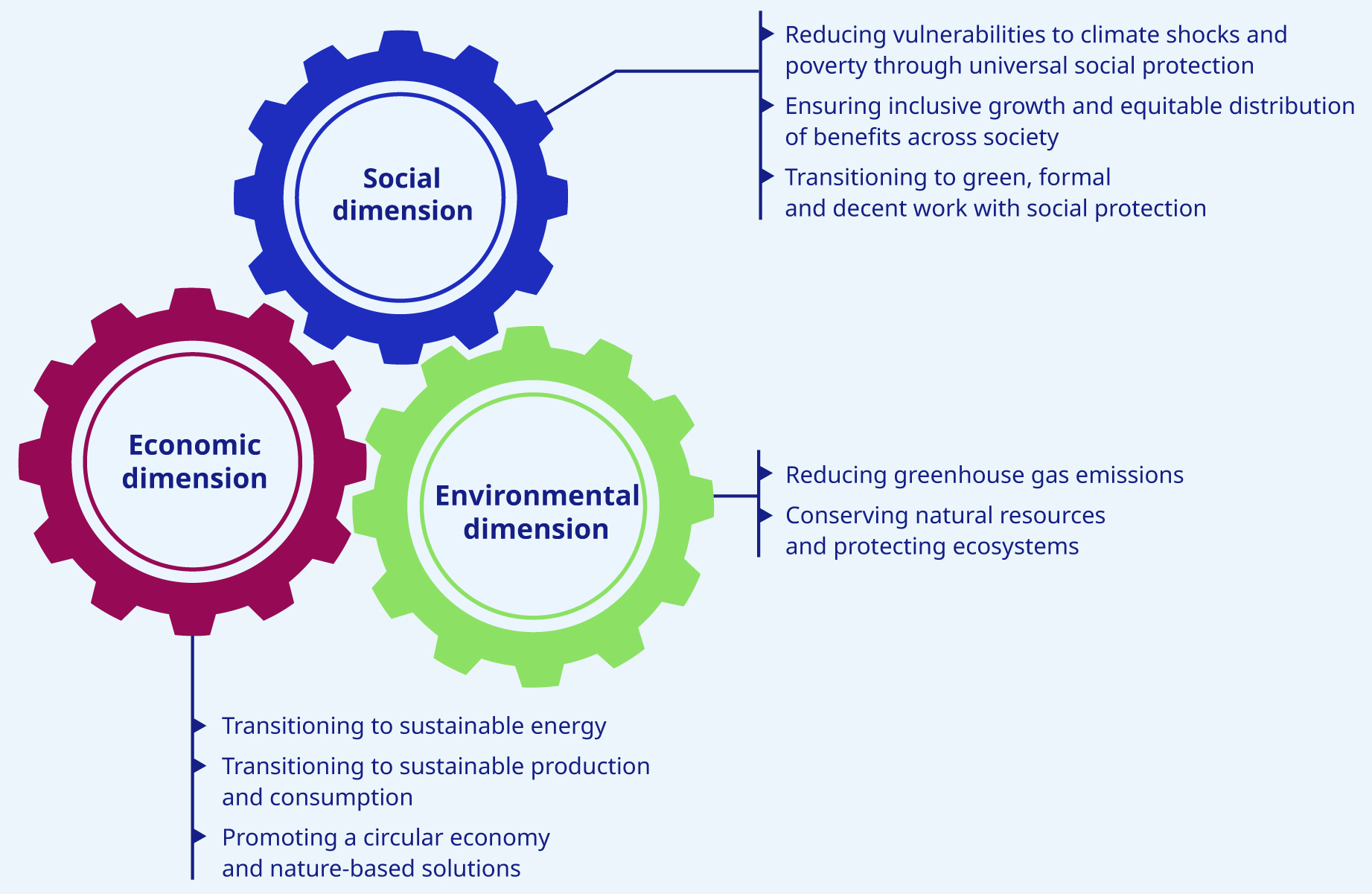

Social protection plays a central role in a just transition to environmentally sustainable economies and societies, and as an enabler for both climate change adaptation and mitigation.

-

Social protection is a fundamental enabler of climate change adaptation. It enhances people’s capacity to cope with climate-related shocks ex ante by providing an income floor and access to healthcare. Social protection contributes to enhanced adaptive capacities, including of future generations, by increasing human development and productive investments. Cash benefits can directly support livelihood diversification and adaptation strategies, particularly when linked to complementary measures.

-

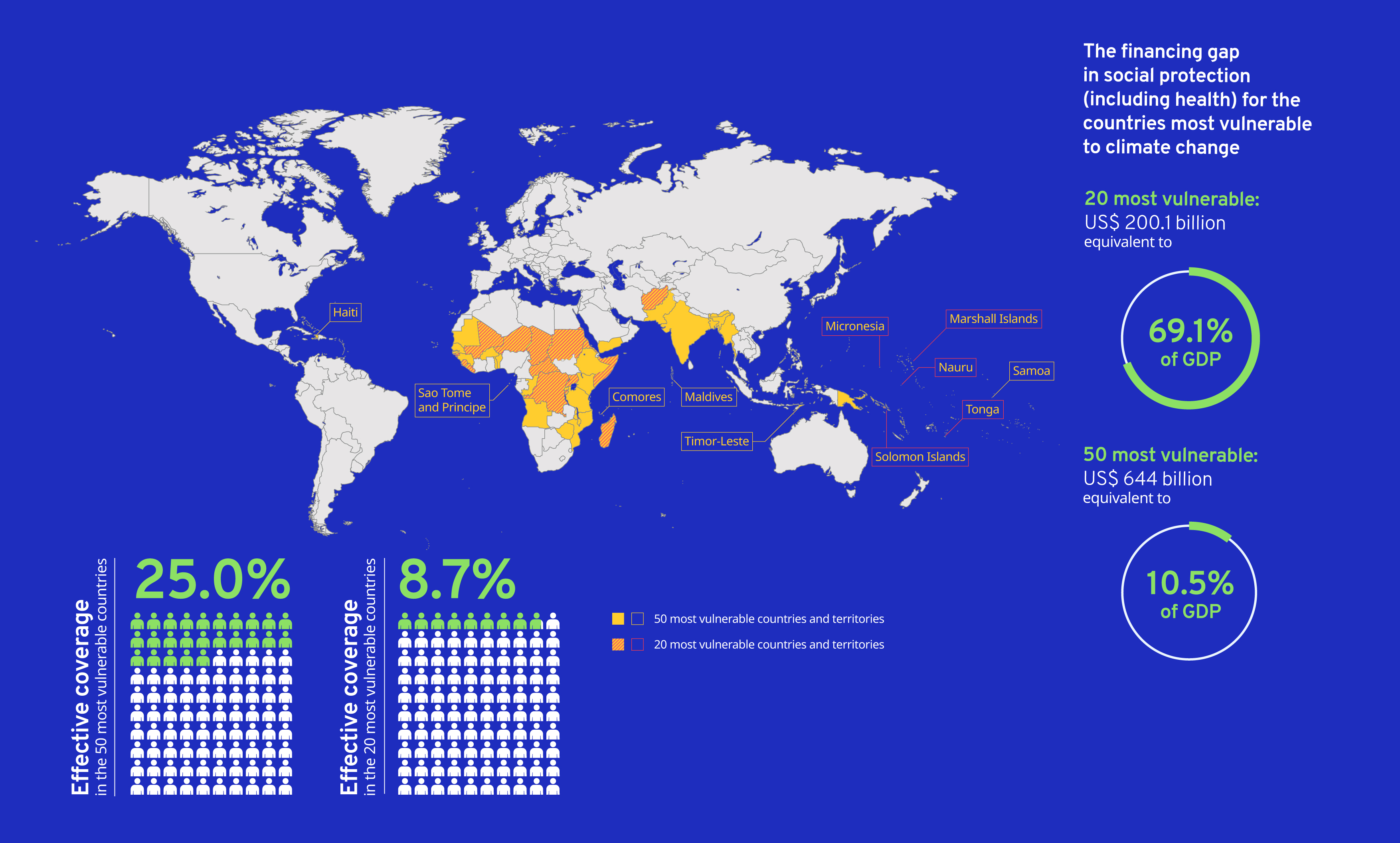

The potential of social protection for adaptation has yet to be realized: coverage is lowest in the countries most vulnerable to climate change. By building universal and rights-based social protection systems, countries can tackle the root causes of vulnerability, including poverty, inequality and social exclusion, thus ultimately contributing to transformative adaptation.

-

Social protection is also a powerful crisis management policy tool providing income security and access to healthcare to address losses and damages. However, many disaster responses utilizing social protection are established on an ad hoc basis. Greater efforts are required to strengthen institutional, financial and operational capacities to ensure more effective, inclusive and predictable shock responses. High-coverage social protection systems are better able to respond to climate-related shocks than those relying on temporary and narrowly targeted “safety nets”.

-

Social protection is key for compensating and cushioning households, workers and enterprises from potential adverse impacts of mitigation and other environmental policies. When combined with active labour market policies, it can help people transition to greener jobs and more sustainable economic practices. Social protection benefits can also be expanded to compensate people for higher prices resulting from carbon taxes or fossil fuel subsidy reform. This is important from an equity perspective, but also for instrumental reasons: by ensuring no one is left behind, social protection, underpinned by strong social dialogue, helps garner the necessary public support for climate policies.

-

Social protection can also directly support mitigation efforts through the greening of public pension funds (that is, divestment from fossil fuels) and the provision of income support to incentivize the conservation and restoration of crucial carbon sinks including forests, mangroves or soils.

.2.1 Social protection for a people-centred adaptation and loss and damage response

2.1.1 Reducing vulnerability through social protection

Vulnerability is one of the main drivers of climate risk, meaning that socio-economic factors determine how severely people are impacted by climate hazards (for example, extreme or slow-onset events) (IPCC 2023a). Vulnerability to climate risks is driven by: (a) sensitivity to being negatively impacted; and (b) a lack of capacity to cope and adapt (IPCC 2023a). For example, older people have greater physical sensitivity to extreme heat, and children to insufficient food and nutrition, especially in utero. Coping and adaptive capacity is influenced by limited resources, social and financial capital, knowledge and information. These tend to be lower for poorer people, women, persons with disabilities, workers in the informal economy, migrants and indigenous populations.

Adaptation actions increasingly focus on reducing vulnerability and strengthening the resilience of people and societies (see box 2.1). However, many actions remain incremental. Transformative system-wide changes are required to address the root causes of vulnerability, which are invariably linked to poverty, the exclusion of vulnerable groups and structural inequalities (Eriksen et al. 2021; Scoones et al. 2020).

Social protection is recognized as fundamental for reducing vulnerability to climate risks and a core adaptation strategy (box 2.2).

Box 2.1 Climate resilience conceptual framework – coping, adaptive and transformative capacities

|

IPCC (2023a) defines resilience as the capacity to cope with a hazardous event, trend or disturbance while maintaining not only the essential function, identity and structure of social, economic and ecological systems, but also maintaining a capacity for adaptation and learning, and/or for transformation. To build resilience, coping (absorptive), adaptive and transformative capacities need to be strengthened (Béné et al. 2012); focusing on coping capacities alone is insufficient. |

Box 2.2 Social protection in the Global Goal on Adaptation and its monitoring framework

|

The 2015 Paris Agreement established a global goal on adaptation “to enhance adaptive capacity, strengthen resilience and reduce vulnerability to climate change” (UN 2015). At COP28, countries adopted seven thematic adaptation targets, including:

The next step will involve the definition of indicators to measure progress towards the global adaptation goals and to estimate financing needs for adaptation. |

Figure 2.1 Breaking the poverty–environment trap through social protection

Source: Adapted from IPCC (2022).

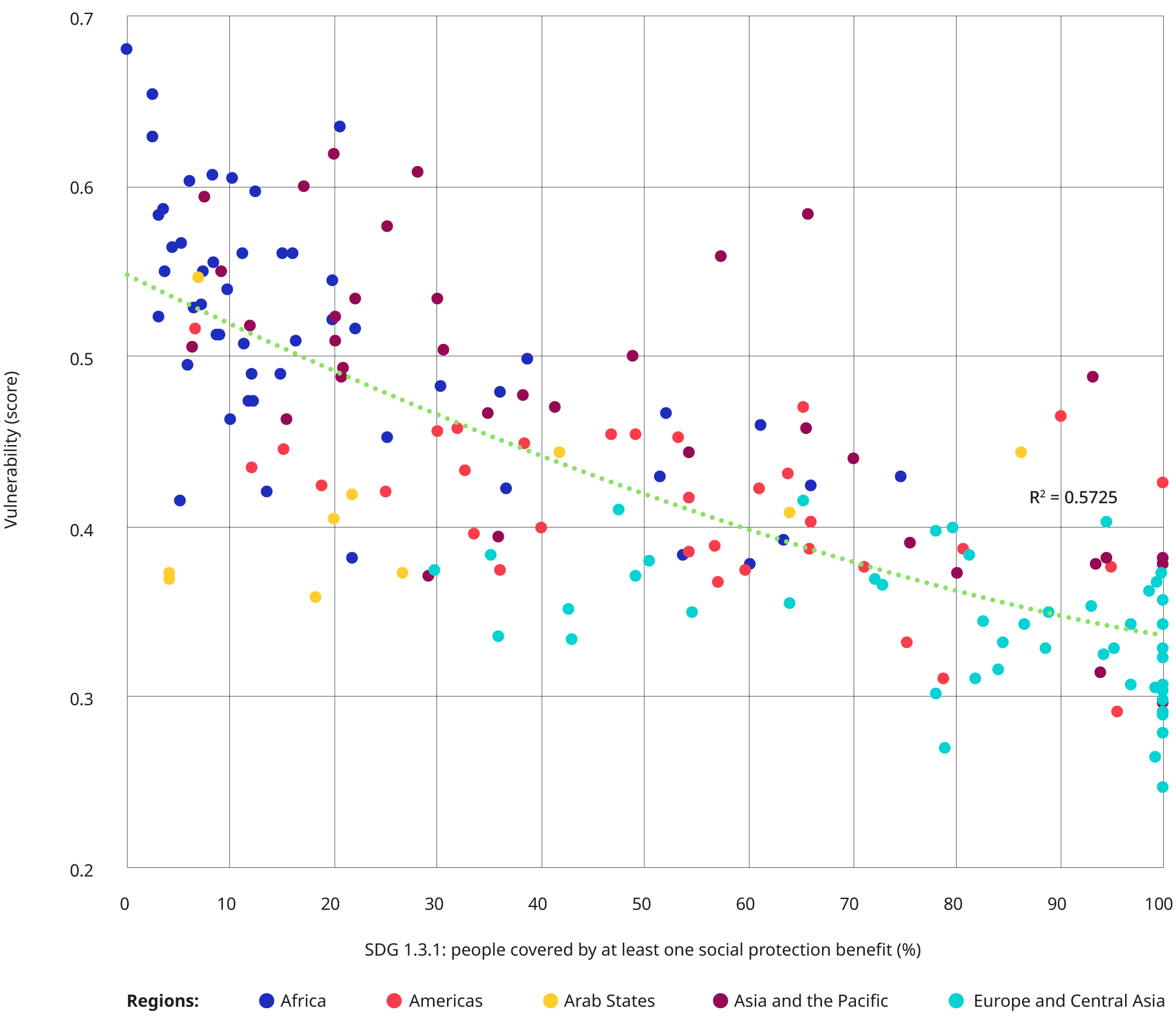

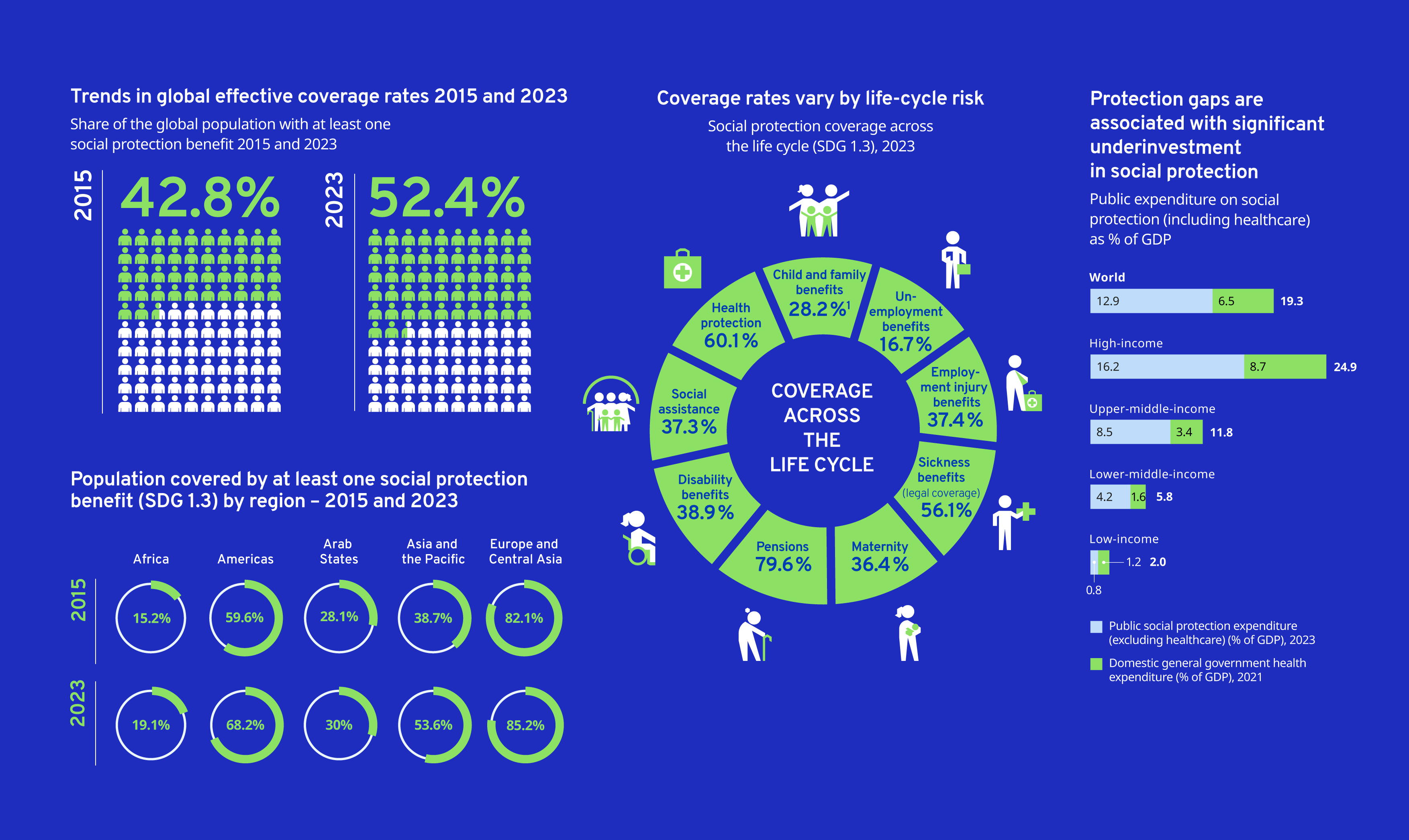

By providing income security and access to healthcare across the life cycle, social protection can help to break the “poverty-environment trap”, which otherwise results in a vicious cycle where increasing climate impacts further exacerbate vulnerability (figure 2.1). Social protection contributes to building the coping and adaptive capacities of people and societies. In addition, a rights-based approach, in which all members of society are entitled to at least a minimum level of social security, can contribute to the transformative changes required by adaptation efforts (Tenzing 2020) (see boxes 2.3 and 2.4). Yet, social protection coverage is lowest in countries most vulnerable to climate change, which makes its expansion particularly urgent (figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2 The relationship between a country’s vulnerability (score) to climate change and social protection coverage (percentage), by region, 2023

Note: A country’s

Source: Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative Country Index and ILO World Social Protection Database.

2.1.2 Prepare, respond, recover: Addressing climate-related shocks through social protection

There is an extensive body of evidence that shows that social protection systems can enhance the capacity of individuals and societies to prepare for, cope with and recover from shocks (Bastagli et al. 2016; Tirivayi, Knowles and Davis 2016).

An ounce of prevention: Increasing coping capacities ex ante

Regular predictable benefits, such as child benefits, old-age pensions, disability benefits and social assistance, increase food security, consumption and savings (Bastagli et al. 2016). During shocks, such benefits act as income floors, helping to maintain a basic standard of living and preventing negative coping strategies (for example, restricted food intake, selling productive assets, child labour or child marriage). Social protection contends with idiosyncratic shocks (that is, individual shocks) and covariate shocks (that is, mass shocks). The COVID-19 pandemic showed that schemes designed for stable periods constitute essential automatic stabilizers during crises (ILO 2021q; Banerjee et al. 2020). For example, the Plurinational State of Bolivia’s quasi-universal non-contributory pension prevented food insecurity and a decline in food consumption for older people and multigenerational household members, especially for low-income households (Bottan, Hoffmann and Vera-Cossio 2021). This also illustrates how social protection acts as a key social determinant of health and well-being where climate change is anticipated to increase health inequity (Jay and Marmot 2009).

Social protection schemes can enhance people’s capacity to cope with extreme weather events (Agrawal et al. 2020). Zambia’s child benefit partly offsets the negative caloric impact of low rainfall, particularly for the poorest households (Asfaw and Davis 2018). In Ghana, regular cash benefits mitigated the impact of prenatal exposure to extremely high temperatures on birthweight by improving the nutrition and food security of pregnant women (LaPointe et al. 2024). Existing social assistance helped protect income and consumption during floods and earthquakes in Indonesia (Pfutze 2021; Fitrinitia and Matsuyuki 2022) and drought inNiger (Premand and Stoeffler 2020).

Social health protection increases the coping capacity of households by facilitating access to healthcare without hardship and by reducing the need for out-of-pocket health expenditures (see section 4.4). This is particularly important considering the impact of the climate crisis on the prevalence and transmission of diseases, which can pose a major health security risk (see section 2.1.3). Estimates show that climate-related health impacts are the most significant drivers of climate-induced poverty increases in both Latin America and the East Asia and Pacific region (Jafino et al. 2020).

The importance of reducing vulnerability to climate shocks ex ante, particularly for vulnerable groups, cannot be overstated. Increasingly frequent extreme events and intensifying slow-onset changes threaten people’s livelihoods, health and well-being. These are not limited to acute crises that can be addressed through temporary emergency measures, but require systemic responses (Kaltenborn 2023). As some extreme events are more severe than what existing benefits can cushion (Banerjee et al. 2020), social protection systems need to be sufficiently flexible and adaptive to expand and ensure income security and access to healthcare in disasters (see box 2.4).

Leveraging social protection systems to respond to climate-related shocks, including losses and damages

When appropriate design, institutional and operational capacities are put in place ex ante, social protection systems can provide predictable (additional) support to those affected by climate-related shocks by ensuring:

-

adequacy in the context of increased needs by temporarily adjusting benefit values/packages, frequency or duration (vertical expansion);

-

coverage of all those affected by modifying eligibility rules of existing schemes or introducing/activating (new) emergency schemes (horizontal expansion); and

-

comprehensiveness and complementary services to cover individuals’ multidimensional needs and the support required by enterprises.

Box 2.3 Addressing climate change–related losses and damages through social protection

|

Social protection can help address economic losses related to income and non-economic losses, including health-related losses.1 The universality and portability of social protection benefits also guarantee an adequate standard of living during climate-induced displacement. In loss and damage discourse, there is a tendency to reduce the role of social protection to be merely a delivery channel for emergency support once shocks have struck. This interpretation fails to appreciate that:

Hence, technical and financing arrangements for loss and damage response – including the Loss and Damage Fund agreed on at COP28 – should, where necessary, reinforce the capacities of social protection systems in order to make them more universal and adaptive. 1 Non-economic losses can have economic consequences and economic solutions. For example, losses related to health result in financial hardship, and debt and income losses that can be contained through social health protection. |

Leveraging social protection systems to respond to climate-related shocks, including in the context of loss and damage (see box 2.3) can have a range of potential advantages over unintegrated disaster and humanitarian responses (ILO, forthcoming e), including:

-

faster and more efficient responses;

-

more sustainable and predictable responses, especially where chronic humanitarian caseloads and humanitarian funding fluctuates;

-

contributions to investments in national systems and to building social protection floors; and

-

opportunities to embed programmes within national legal frameworks and promote rights-based social protection even during emergencies.

The extent to which a social protection system can complement and ideally reduce the need for humanitarian and disaster risk management support depends on how well prepared it is to provide a prompt comprehensive response. Regardless of who provides emergency support, it is important to coordinate and align social protection with humanitarian and disaster risk management responses. This avoids creating inefficient parallel systems and ultimately generates better outcomes (O’Brien et al. 2018; UNICEF 2019).

Social protection systems can help respond to climate-induced shocks by adapting and expanding various schemes. Therefore, thinking about the whole system as adaptive, and not only in terms of a flagship scheme, is key (see box 2.4).

From ad hoc to institutionalized responses to climate-related shocks

Some countries increasingly choose to temporarily expand existing social protection schemes to provide additional support to people affected by extreme events (Costella and McCord 2023). In Fiji, the Government topped up existing social assistance and social pension schemes when Cyclone Winston hit in 2016 (Mansur, Doyle and Ivaschenko 2017). In the Philippines, child benefits provided by the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (4Ps) were raised in response to several disasters.

Box 2.4 Shock-responsive and adaptive social protection

|

There has been growing interest in the role of social protection in addressing the impacts of climate change and other crises. Different approaches have emerged:

These approaches have prompted important innovations for improving the institutional, financial and operational capacities of social protection systems for better preparedness and responsiveness. However, the proliferation of evolving concepts – often defined differently by different agencies and countries – has sometimes created confusion regarding their definition and role vis-à-vis more established concepts of social protection (FAO, ILO and UNICEF 2022, box 11). Some argue that social protection is inherently “shock-responsive”, as good systems automatically expand when need increases (Freeland 2021). While conceptually true, this argument overlooks the reality of many countries, particularly those most vulnerable to the climate crisis, where social protection systems are insufficiently developed to be responsive or adaptive. As different sectors increasingly employ the terms “shock-responsive social protection” and “adaptive social protection”, including those working on climate action, further clarification can help:

|

Sources: ILO (forthcoming e); WFP (2020).

Where social protection coverage is already high, and administrative capacity exists, a large part of the affected population can be reached by the in-built provision of emergency extension, advanced payments, exceptional financial support or top-up payments to existing beneficiaries of different life-cycle schemes (see box 2.5). However, when there is a large, uncovered population both in terms of legal and administrative coverage, it is more difficult to reach all those affected by a climate disaster. Some countries have temporarily extended cash benefits to uncovered populations after a disaster, but such expansions are generally more difficult to implement in an inclusive, timely and predictable way (O’Brien et al. 2018). Particularly where poverty-targeted schemes are leveraged to respond to climate-related shocks, there is a high risk of carrying existing exclusion errors into emergency responses. Emergency basic income schemes for reaching all those affected by an extreme event may be another option (see box 2.6).

It is encouraging that countries are increasingly using social protection systems to respond to climate-induced shocks. However, many responses are still established on an ad hoc basis, as systems and schemes are insufficiently prepared. Going forward, it will be crucial to further strengthen institutional and operational capacities to ensure greater predictability and institutionalized shock responses (see box 2.4). This means eligibility criteria, transfer value and duration, payment triggers and financing are predefined, and these parameters are anchored in laws, policies and standard operating procedures (see sections 3.4.3 and 3.5). Engaging social partners in this process is important for collective buy-in and ensures more inclusive responses.

Box 2.5 Brazil’s systems-wide social protection response to floods in 2024

|

In April and May 2024, heavy rains resulted in severe flooding in the Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul, affecting some 2 million people. The Government implemented the following measures to ensure income security and to support recovery:

|

Source: Government of Brazil (2024).

Box 2.6 Emergency basic income: A “stability and reconstruction benefit” for extreme events?

|

Emergency basic income is defined as a regular cash payment, paid individually to all residents or people living in an affected region for the duration of any given crisis. In the COVID-19 response, one country – Tuvalu – used an emergency basic income and 11 countries/territories deployed a quasi-universal emergency basic income.1 For instance:

Emergency basic income demonstrates high transparency, administrative ease, limited risk of exclusion error and deployment rapidity (if it is an existing feature of systems) to support people in rebuilding their lives and livelihoods, and kick-start macrorecovery. During crises, it could be a strong expression of a resourced social contract. 1 Guyana, Hong Kong (China), Israel, Japan, Jersey (dependency of the United Kingdom), the Republic of Korea, Serbia, Singapore, Taiwan (China), Timor-Leste and the United States (Gentilini 2022). |

Sources: Based on Bricker et al (2023); ISSA (2014); Orton, Markov and Stern-Plaza (2024); United States (2023).

Box 2.7 Providing predictable trigger-based income security in drought-prone regions

|

Since 2009, the Hunger Safety Net Programme has been providing regular income support to chronically food-insecure households in Kenya’s northern counties. The Hunger Safety Net Programme is supported by contingency procedures and funds, which allow it to provide temporary support to additional households during drought and flooding. Vulnerable households are preidentified and registered. Operational guidelines define when and how these households receive temporary emergency support when a shock strikes. Responses are triggered by a vegetation condition index. This allows the system to deliver assistance within ten days of an emergency being declared, which is timelier than humanitarian aid where, often, three to nine months elapse before beneficiaries are reached (Merttens et al. 2018). The Hunger Safety Net Programme is coordinated with the Kenya Livestock Insurance Programme, an index-based livestock insurance subsidized by the Government. The two programmes share the same data for triggering payouts, complementing each other within a broader social protection strategy (FAO 2021). |

Some countries are already moving towards providing more predictable social protection support in the context of extreme events. National schemes are thus being designed to tackle chronic deprivation or (seasonal) unemployment/underemployment with mechanisms for scaling up support during extreme events (see box 2.7). Such schemes are increasingly linked to predefined triggers, such as drought indices or extreme temperature forecasts. The United Kingdom’s cold weather payments to vulnerable households are triggered when the meteorological office forecasts extreme cold (Etoka, Sengupta and Costella 2020). Employment guarantees, such as India’s National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, can also provide seasonal income security, while others, such as the Philippines’ Integrated Livelihoods and Emergency Employment Programme, can provide emergency employment for workers affected by crises and disasters (ILO and AFD 2016).

Box 2.8 Transitioning crisis-affected populations from emergency assistance to inclusion in Mozambique’s national schemes

|

Mozambique’s COVID-19 response involved activating the Post-Emergency Direct Social Support Programme. This provided temporary income support to over 1 million people lacking social protection at the time. Many people receiving the COVID-19 support were also eligible for other existing category-based schemes (for example, for children and older people), but were not receiving these owing to budgetary limitations. Many had been on waiting lists for years or never been registered. With joint ILO–IMF support, the Government increased the domestic resource allocation to the non-contributory pillar of the social protection system in 2023. This increased coverage from 600,000 to 1 million people, transitioning many from temporary emergency support to more regular and predictable benefits. This allows for a more effective crisis recovery and helps reduce vulnerability to future crises, including climate-related disasters (for example, droughts and cyclones) regularly affecting Mozambique. |

Sources: Lima Vieira, Vicente Andrés and Monteiro (2020); ILO (2024c).

Finally, the crisis recovery phase should always be used as an opportunity to close coverage gaps, by assessing the possibility of enrolling those temporarily covered into existing schemes on a more permanent basis (see box 2.8). This will sustainably reduce vulnerability to future climate-related shocks.

Integrating climate risks into contributory schemes

Climate risks impact workers’ health and welfare and can be factored into social insurance schemes. In Algeria, for example, the Caisse Nationale des Congés Payés et du Chômage Intempéries des Secteurs du Bâtiment, des Travaux Publics et de l’Hydraulique (National Fund for Paid Leave and Weather-Related Lay-offs in the Construction, Public Works and Hydraulics Industries) provides a wage replacement for workers in the construction sector for unworked hours during bad or severe weather events, including extreme heat, which is financed by workers’ and employers’ social insurance contributions (ISSA 2019). Luxembourg and Switzerland also have bad-weather benefit schemes which complement regular unemployment protection, and are financed exclusively by employers (Government of Luxembourg n.d.; SECO 2024). In the United States, the Disaster Unemployment Assistance programme, administered by disaster authorities, provides assistance via state unemployment funds to people otherwise ineligible for unemployment insurance compensation, including self-employed people who have lost their income due to a declared disaster.1

In addition, the design of contributory schemes can be temporarily modified to provide better services in the context of climate-related shocks (Sengupta, Tsuruga and Dankmeyer 2023). Adaptations could include delaying or reducing contributions, freezing contribution rates or subsidizing contributions to ensure continued social security contributions and financial breathing space for employers and employees. Furthermore, advanced pensions payments can provide important short-term relief. The Philippines was an early adopter of such adjustments, owing to its exposure to frequent climate shocks (see box 2.9). However, caution is required with exceptional one-off pension fund withdrawals, as was the case in Fiji and Jamaica after storms occurred (Sengupta, Tsuruga and Dankmeyer 2023). Such measures may jeopardize the adequacy of future retirement income if not replaced and, also carry equity risks if tax financing covers any deficit (ILO 2020c; Orton 2012).

Box 2.9 Ahead of the curve: The Philippines

|

When disasters strike, the Philippines’ social insurance institutions and other government departments deploy additional measures to support affected populations, such as:

|

Sources: ISSA (2014); Sengupta, Tsuruga and Dankmeyer (2023).

Providing support to enterprises and protecting jobs during climate-induced shocks

Increasingly frequent and severe extreme events are leading to business interruption and even temporary closure of workplaces. This may require enterprises to effect redundancies or even shut down entirely, creating costs for individuals and the economy. Social protection can help support business continuity and complement wider support for selected enterprises.

For enterprises to resume activity and make a swift recovery, financial pressures must be temporarily alleviated to avoid shedding workers and to maintain the employment relationship. Options include temporarily reducing or freezing social insurance contributions, provided these are paid later upon resumption of activity. Employment relationships can also be maintained through temporary worker retention or furlough schemes, short-time work or temporary unemployment schemes. These mechanisms were widely used in the COVID-19 pandemic. However, they pertain more to high-and middle-income contexts, as their costs are substantial and, in some countries, they require large additional tax financing. Equity considerations are also important, especially in contexts where large parts of the population are adversely affected, not just workers and enterprises (Orton, Markov and Stern-Plaza 2024). Striking a balance between enterprise continuity support and wider societal support is key, and the decision depends on the magnitude of the effects of an extreme event.

Providing protection in the context of climate-induced forced displacement

In 2022, an estimated 108.4 million people were forcibly displaced – the largest escalation since UNHCR record-keeping began (UNHCR 2022). Climate change is exacerbating displacement trends, through other drivers such as persecution, conflict and violence. Over half of internally displaced people were displaced by sudden-onset events (for example, cyclones). Concurrently, slow-onset climatic events (for example, sea-level rise and drought) have degraded ecosystems, adversely affecting agricultural communities. This leads to migration and displacement (Chazalnoël and Randall 2021). Both event types disrupt livelihoods, displace people and heighten intercommunal tension over dwindling resources (Lenton et al. 2023). The multiplication of crises, including protracted ones, underscores the urgency of extending the reach of social protection systems to include forcibly displaced persons – migrants, refugees, asylum seekers and internally displaced persons.2

Box 2.10 Inclusive social health protection systems to bridge the humanitarian-development nexus

|

A number of countries have pledged to include refugees on par with nationals in their social health protection schemes to ensure greater access to health services and improve the health status of refugees and host communities alike. To support those commitments, the ILO and the UNHCR have been collaborating on the extension of social health protection to refugees for over a decade. Inclusion was supported in 12 countries in the Africa region. More recently, the two agencies have joined forces and combined their respective areas of expertise to support transitions out of camp-based assistance and the strengthening of social health protection systems simultaneously. Discussions in this regard are ongoing in Egypt, Ethiopia and Kenya (ILO 2021k; ILO and UNHCR 2023; ILO and NHIF 2023). This partnership has also progressively opened the door to discuss inclusion in the wider context of social protection extension for additional benefits (Government of Kenya 2023; ILO and UNHCR, 2024). |

Sources: ISSA (2014); Sengupta, Tsuruga and Dankmeyer (2023).

International instruments3 recognize the human right to social security for refugees and social security standards provide guidance for materializing their equal treatment within national systems (ILO, ISSA and ITCILO 2021; ILO 2024d). Yet, forcibly displaced persons tend to face unique difficulties in accessing social protection, including: exclusion from legal frameworks or in practice; geographical barriers (many refugees and asylum seekers live in remote areas or refugee camps); lack of awareness of their rights and how to avail those rights; and complex administrative requirements (language barriers, no identification documents) (ILO 2021j). Furthermore, they are disproportionately represented in vulnerable employment due to labour market discrimination. This affects their social insurance coverage. In many host countries, social protection systems are nascent or underdeveloped, which limits de facto access for forcibly displaced persons (ILO, ISSA and ITCILO 2021). Integrating forcibly displaced persons into national schemes avoids creating parallel systems and undermining social cohesion with host communities (ILO, ISSA and ITCILO 2021).

As displacement becomes increasingly extended with the climate crisis, transitioning from primarily response-based operations to national system-strengthening approaches is key (ILO 2022f). While recognizing the importance of delivering direct assistance to meet the immediate needs of displaced populations (for example, cash transfers and emergency access to healthcare), inclusive national systems provide an opportunity to bridge the divide between development and humanitarian actors (see box 2.10).

2.1.3 Supporting inclusive adaptation and transformation through social protection

Increasing adaptive capacities and facilitating livelihood adaptation

Social protection benefits also help strengthen adaptive capacities (Godfrey Wood 2011; Béné et al. 2012; Bowen et al. 2020; Sengupta and Costella 2023). While the capacity to cope and adapt are intrinsically connected to each other, coping capacity is often associated with the immediate impacts of a shock, whereas adaptive capacity alludes to a longer time horizon and implies that some learning, adaptation or even transformation is taking place (Burkett 2013).

Social protection strengthens “generic adaptive capacity” through well-documented positive impacts on fundamental human development outcomes (see section 1.2) (Eakin, Lemos and Nelson 2014). Well-designed child benefits, especially when combined with complementary social services, can have positive impacts on children’s education, health status and nutrition, thereby increasing the adaptive capacities of future generations (ILO, UNICEF and Learning for Well-Being Institute 2024). Maternity protection, including healthcare and cash benefits, is similarly important for supporting the health and nutrition of mothers and newborns (ILO 2021q). Old-age pensions, disability benefits or social assistance can also contribute to human development and support social determinants of health equity. Research shows that higher generic capacity corresponds to higher levels of climate-specific adaptive capacity (Lemos et al. 2016).

Cash benefits can contribute to productive investments and livelihood diversification strategies, sometimes decreasing reliance on climate-sensitive livelihoods (Bastagli et al. 2016; Asfaw and Davis 2018; Sengupta and Costella 2023). Evidence shows that non-contributory social protection can support resilient and inclusive agricultural growth (Correa et al. 2023). Old-age and child benefits in Bangladesh and Zambia, respectively, were shown to result in increased purchases of agricultural assets (for example, tools and seeds), while helping beneficiaries invest in non-farm enterprises (FAO 2015; Begum et al. 2018).

However, income support or substitution alone is often insufficient to achieve a full and effective transition to more climate-resilient livelihoods and production practices (Costella et al. 2023; Lemos et al. 2016). Without appropriate guidance, beneficiaries’ investments could even lead to maladaptation, locking them into climate-sensitive livelihoods and, thus, further increasing vulnerability (Tenzing 2020).

Social protection schemes work best in contributing to effective long-term adaptation when they are linked with complementary services and measures specifically designed to address climate risks (Aleksandrova 2019; Costella et al. 2023). Such measures may include climate-sensitive livelihoods promotion and diversification programmes. These include agricultural extension services for vulnerable farmers, in-kind transfers (for example, drought-resistant seeds and tools), crop, livestock or other specific agricultural insurance, or education and training for sustainable fishing or agriculture (Tenzing 2020). Providing people with income security while they participate in adaptation-specific labour market programmes, supports productive risk-taking behaviour and forward planning.

Social protection creates important enabling conditions but is insufficient alone for climate change adaptation (Godfrey Wood 2011; Tenzing 2020). Adaptation actions involving the improvement of institutions, physical infrastructure or the state of the natural environment are necessary to further reduce vulnerability, exposure and hazards (see figure 2.1). The promise of social protection lies in ensuring that everyone, including the most vulnerable, gains from climate change adaptation measures.

Transformative adaptation through universal coverage and rights-based social protection

Climate change adaptation literature increasingly argues that system-wide transformations are necessary to tackle the root causes of vulnerability. Moreover, adaptation efforts characterized by time-bound, donor-driven projects merely facilitate “incremental” adjustments to the risks from the climate crisis (Pelling, O’Brien and Matyas 2015). However, “transformative adaptation” has rarely been considered in adaptation policies, plans and policies to date (Fedele et al. 2019).

Rights-based protection providing adequate and comprehensive benefits can help tackle some structural inequalities that primarily drive vulnerability (Tenzing 2020; Kundo et al. 2024), including gender-related inequalities (see box 2.11). However, in many countries, this potential has yet to be realized because social protection provision is insufficient to achieve the desired transformative adaptation outcomes due to low coverage, inadequate benefit levels, insufficient financing, poor governance and a failure to address unequal gender norms and other power relations (Desai et al. 2023; Kundo et al. 2024).

Therefore, it is imperative that lower-income countries gradually shift away from an over-reliance on narrowly poverty-targeted schemes for (extremely) poor households (typically called social safety nets), which, at best, play an incremental but not transformative role in reducing vulnerability to climate change.

Box 2.11 Addressing gendered climate impacts through social protection

|

Gender-responsive social protection is needed to inform responses to gendered climate impacts. Not only are there large gender inequalities in effective coverage, women and girls are disproportionately affected by climate risks through multiple channels: their dependence on livelihoods based on natural resources and agriculture; the existing burden of unpaid care work; lower incomes and limited assets (Nesbitt-Ahmed 2023); and a higher likelihood of being adversely affected by environmental disasters and shocks. The latter manifests as lower life expectancy, health complications and gender-based violence (Erman et al. 2021). Having access to comprehensive provision is an important starting point, but specific adaptations are needed to increase the gender-responsiveness of social protection, namely: gender-based increments (Gavrilovic et al. 2022); individualized – as opposed to household – social assistance payments; the minimization of transaction costs when enrolling in schemes; and scope for integrated economic and social policies (Razavi et al., forthcoming a). |

-

The high exclusion errors of poverty-targeted schemes are well documented (Kidd and Athias 2020), including in countries in extremely climate-vulnerable regions like the Sahel, where poverty-targeting methods were found to perform “no better than a random allocation of benefits” (Schnitzer and Stoeffler 2021).

-

Poverty is not the only factor driving climate vulnerability (Doan et al. 2023). Inequality and marginalization drive monetary and multidimensional poverty and underlying vulnerability (Sabates-Wheeler and Devereux 2007). In fact, the number of people vulnerable to climate change – approximately 3.3 to 3.6 billion people (IPCC 2023a) – far exceeds the number of people living in chronic poverty. This further puts into question the merits of poverty targeting for reducing climate vulnerability (Costella and McCord 2023).

-

Climate change further increases the dynamic nature of poverty, meaning that the preventive function of social protection becomes even more important: providing support to reduce existing vulnerability prevents it from being exacerbated further by climate change and stops people from falling into poverty. This runs contrary to providing support only retrospectively by trying to target those who are already poor. Recurrent climate-related shocks will make it more challenging to maintain the accuracy of the data used for poverty-targeted schemes as people may move in and out of poverty more frequently.

-

Poverty targeting can result in low social protection coverage in urban areas, potentially leaving people affected by climate-induced displacement unprotected. Chronic poverty rates are typically higher in rural areas (World Bank 2015), but as climate change puts pressure on rural livelihoods, rural–urban migration is expected to increase (IPCC 2023a). Informal urban settlements are especially exposed to disaster risk and face a host of climate-related vulnerabilities while struggling with low coverage (Aleksandrova 2020).

This is not to say that poverty-targeted schemes have no role to play in comprehensive social protection systems. However, they can be enhanced and should constitute a residual rather than main strategy for harnessing the potential of social protection for reducing climate vulnerability and building resilience.

Instead, countries should progressively build rights-based universal and adaptive social protection systems, which are usually achieved through a combination of contributory and tax-financed schemes that systematically provide fundamental and adequate protection for everyone (see box 2.12).

Box 2.12 Including indigenous communities in social protection systems

|

Indigenous communities represent 6 per cent of the world’s population but 19 per cent of those living in poverty globally (ILO 2022h). They are the most impacted because of their vital ties with land and water resources, especially people living in small island developing States (UNESCAP and Government of Samoa 2020). Indigenous peoples possess the traditional knowledge of using environmental resources, adapting to and mitigating climate risks. However, abusive occupation of land and exploitation of natural resources, which increase the impact of climate change, threaten the survival of those communities. Social protection can play a role in remedying structural injustices and displacement. The cultural appropriateness of the policies developed in consultation with the peoples concerned, and the respect for their collective rights to their livelihoods and land, need to be included (Errico 2018; Cooke et al. 2017). For instance, Paraguay’s non-contributory pension exempts indigenous people from proving their poverty status, recognizing the multiple and specific vulnerabilities they face, including in the context of climate change (Errico 2018). |

Building resilience to health security threats exacerbated by the climate crisis

Changes in temperature and precipitation patterns due to climate change impact animal life in various ways. For instance, mosquitoes, ticks and bats may carry and transmit pathogens to humans, causing malaria, dengue, Rift Valley fever, Lyme disease and other infectious diseases to spread more easily and reach new geographic areas (Mora et al. 2022). The consequences of climate change, such as human displacement, insufficient water and difficulties accessing it, difficulties accessing nutritious food in certain areas, and the concentration of populations in areas with resources, are also anticipated to impact current transmission pathways for a wide range of pathogens affecting human health (Mora et al. 2022; McMichael 2015). Therefore, climate change is increasing health security threats. Consequently, prevention, preparedness and response need to be strengthened and rethought in order to overcome new challenges (Khor and Heymann 2021; Carlson, Albery and Phelan 2021).

Prevention, preparedness and response strategies should include social protection and support the building of sustainable health and social protection systems (USP2030 2023b). For example, social protection systems that achieved high population coverage before the COVID-19 crisis responded more effectively to the pandemic and other epidemics than those with narrow coverage (ILO 2021q). The most affected population groups were also disproportionately represented in social protection coverage gaps – typically informal workers, women, displaced populations, older persons, persons living with disabilities and chronic conditions, migrants and essential workers. This demonstrates the urgent need for protection to be made universal (ILO 2023x). Immediate responses also tended to offer little coverage for non-nationals (ILO 2020f).

A global review of the evidence on the COVID-19 response shows that social protection schemes played a positive role in cushioning the socio-economic impacts of public health and social measures, especially when adequate benefits levels were provided (WHO, forthcoming a). Similarly, the pandemic illustrated the need for comprehensive systems offering social protection benefits that can contribute significantly to prevention, preparedness and response – such as sickness benefits. Unfortunately, these benefits currently exhibit large coverage gaps (see section 4.2.3), which were highlighted during the N1N1, SARS and COVID-19 pandemics. Indeed, sickness cash benefits are central for ensuring compliance with public health and social distancing measures, and for ensuring income security when quarantining and halting disease transmissions (ILO 2020e; James 2019).

As a new international legal instrument on pandemics is on the agenda of the United Nations, it is important to underline that building resilient societies prepared to face health security threats requires closely coordinated universal health and social protection systems. Such systems are codependent and core enablers of effective prevention, preparedness and response. The global financing put at the disposal of countries to foster prevention, preparedness and response should act as a trigger in this respect and avoid the pitfalls of the humanitarian-development nexus, which does not necessarily lead to the long-term strengthening of systems. This is the only way to secure rights-based predictable social protection, which contributes to the resilience of individuals and societies to health security threats.

.2.2 Social protection as an enabler for climate change mitigation and environmental protection

Ambitious climate change mitigation and environmental policies are necessary to reduce emissions towards net zero and protect the planet, its biodiversity and natural resources. Transitioning to more environment ally sustainable societies and economies can deliver positive economic and social outcomes. In fact, the combined shift to low-carbon and circular economies, and sustainable agriculture, could create millions of new decent jobs worldwide (ILO 2023c). However, the prospective gains are not automatic and, unless the necessary policy measures are taken, some mitigation and other environmental policies may lead to temporary disruptions of incomes, jobs and livelihoods.

Social protection plays an essential enabling function in the transition, not only ensuring that no one is left behind, but also actively helping people to reap its benefits. First, it can cushion people from potential adverse welfare impacts of climate policies such as carbon pricing or subsidy reform. Second, particularly when integrated with active labour market, skilling and lifelong learning policies, social protection helps transition workers affected by the transition to greener employment opportunities. Third, social protection can make direct contributions to mitigation objectives through the greening of its own operations, including pension fund investments and through the incentivization of conservation and sustainable practices.

As part of a comprehensive and integrated just transition policy frameworks, social protection can ensure that environmental, economic and social objectives are pursued simultaneously. When combined with effective social dialogue and communication with social partners and the public, social protection measures can be instrumental in acquiring public and politicalacceptance for the implementation of the mitigation and environmental protection policies required to tackle the climate crisis, pollution and biodiversity loss.

2.2.1 Cushioning distributional effects and providing compensation for carbon pricing, including fossil fuel subsidy reforms

A range of climate change mitigation policies will be required to achieve emission reduction goals, including national regulations, (green) subsidies and carbon pricing. While necessary from an environmental perspective, when unaddressed, these policies can have negative financial implications, particularly for low-income households (Malerba et al. 2022).

This section focuses on the enabling role of social protection for two related, yet distinct mitigation policy options:

-

the reform of explicit fossil fuel subsidies (a type of energy subsidy); and

-

direct carbon pricing measures, such as carbon taxes or emission trading schemes (sometimes referred to as implicit fossil fuel subsidies, as their absence subsidizes the usage of fossil fuels).

Both policy reforms are designed to lead to an increase in the prices of carbon-intensive goods and services, thereby creating price signals to incentivize efficient energy usage and the channelling of investment towards cleaner energy technologies (Fugazza, forthcoming; Auffhammer et al. 2016). Both options also create additional fiscal revenues or savings, some of which could be redistributed to households through the social protection system to cushion the impact of price increases. According to the IMF, such reforms could result in CO2 emissions of 43 per cent below baseline levels by 2030, raise revenues worth 3.6 per cent of global GDP, and prevent 1.6 million deaths caused by air pollution annually4 (Black et al. 2023).

Explicit fossil fuel subsidies

In 2021, the Glasgow Climate Pact called on countries to “phase out … inefficient fossil fuel subsidies”, which amounted to more than US$1 trillion of consumer fossil fuel subsidies in 2022 (IEA 2022; 2023).

Fossil fuel subsidies are generally regressive (that is, they are more beneficial for richer households, which tend to spend more on energy-related goods and services). At the same time, the uncompensated removal of such subsidies can have severe negative impacts on low-and middle-income households due to the ripple effect of higher energy prices on food and fertilizer prices (Dorband et al. 2019). It is estimated that the uncompensated removal of fossil fuel subsidies would significantly increase poverty rates in Ecuador, Nigeria, Peru and Tunisia (Malerba et al. 2022; Rentschler 2016; Schaffitzel et al. 2020).

Between 2015 and 2020, over 53 countries undertook fossil fuel taxation and subsidy reform efforts (Baršauskaitė 2022), many of which were accompanied by expansions of the social protection system (Malerba 2023). For example, Morocco gradually phased out most fuel subsidies between 2011 and 2015 and invested part of the savings to expand the coverage of (a) a cash benefit for children from 80,000 to 466,000 families and (b) the social health insurance scheme from 5.1 million to 8.4 million people.

Experiences from countries, including Egypt and Jordan, have shown that when compensation is targeted at only a small number of extremely poor households, it may not effectively prevent welfare losses (Malerba 2022; Abdel Naeem Mahmoud 2018; FES 2023). Approaches that also consider the impacts on the near-poor and the middle class promise to be more effective at preventing spikes in poverty and ensuring more widespread public support for reforms (Shang 2021).

The most appropriate response needs to consider the existing poverty and vulnerability situation, energy consumption patterns, and the existing gaps of the social protection system. Where coverage is already high, increasing the adequacy of existing benefits may be the most effective option, while in other contexts, an expansion of coverage or even comprehensiveness by introducing new schemes could be an alternative (Gasior et al. 2023). Györi and Soares (2018) estimated that, in Tunisia, half of the savings from the removal of fossil fuel and food subsidies could allow for the introduction of a universal child benefit that would be significantly more efficient and effective at preventing and reducing poverty than the subsidies.5

In fact, the progressive removal of fossil fuel subsidies represents an opportunity to close protection gaps and reduce poverty levels even below baseline levels (Malerba 2022; Schaffitzel et al. 2020). Such reforms can create additional fiscal space to expand coverage and adequacy of social protection floors (see section 3.4.3), thereby contributing to the reduction of vulnerability to climate risks and enhancing people’s coping and adaptive capacities (see section 2.1). However, before removing fossil fuel subsidies, the capacity of existing social protection systems to counteract the adverse impacts of these reforms on the most vulnerable households needs to be carefully assessed.

Compensation through social protection systems is instrumental for successful subsidy reforms. Many attempts to reform fossil fuel subsidies have resulted in social unrest. In Ecuador, subsidies had to be reinstated after large-scale protests, which erupted partly because promised compensatory social welfare payments were not delivered on time (IISD 2019). Effective communication campaigns, the delivery of compensation in advance, and engagement in social dialogue can increase the acceptability and transparency of reforms.

Direct carbon pricing schemes

The world is at the beginning of its carbon pricing journey and thus far, mostly industrialized countries have implemented a carbon tax or an emissions trading system, most at relatively low prices. In most cases, households and firms are compensated by lowering other taxes, including income taxes (Marten and Dender 2019). Only a handful have recycled revenues from carbon pricing instruments through the social protection system. For example, Switzerland redistributes two thirds of carbon tax revenues to finance rebates on mandatory health insurance premiums (Mildenberger et al. 2022).

In countries with higher levels of informality and weaker income tax systems, the expansion of non-contributory schemes may be a more appropriate option for compensating people for higher prices as a result of direct carbon pricing schemes (Malerba 2023). However, given that such schemes have not yet been implemented outside industrialized economies and a small number of emerging economies, there is no experience of this to date. Nevertheless, many of the lessons learned with regard to the role of social protection in fossil fuel subsidy reforms also apply to direct carbon pricing schemes:

-

Compensation for welfare losses through the social protection system can be an effective way to prevent spikes in poverty and gain acceptability among the population.

-

Social protection responses that target only the poorest risk being insufficient for cushioning welfare losses: modelling the impact of a carbon tax in Brazil shows that, given current targeting errors, about 20 per cent from the poorest quintile and 50 per cent from the second poorest quintile would experience a net loss if compensation were poverty-targeted (Vogt-Schilb et al. 2019).

-

Redirecting revenues from carbon pricing schemes to the social protection system is an important opportunity for climate justice: taxing those who drive emissions in order to expand social protection to support the adaptation of those who are more vulnerable (see section 3.4.3).

2.2.2 Facilitating a just transition for workers and enterprises

Structural transformations in the context of a just transition

The climate crisis calls for the revisiting of structural transformation pathways that curb greenhouse gas emissions, preserve natural resources and reduce climatic volatility for societies and economies (see box 2.13).

In 2019, ILO estimates indicated that a sustainable energy transition and development of the circular economy could eliminate 78 million jobs while creating 103 million jobs globally (ILO 2019c). More recent ILO data suggests similar trends in the Middle East and North Africa (ILO 2023u), and in Latin America and the Caribbean (Saget, Vogt-Schilb and Luu 2020). These findings suggest overall net positive employment effects, but they mask potential labour market disruptions of the transition. Mismatches in labour demand and supply – that is, temporal, spatial, sectoral and skills – can create frictional and structural unemployment, and asset and livelihood loss. This exacerbates poverty, inequalities and social tension (Gilmore and Buhaug 2021; Malerba 2022; IPCC 2018; HelpAge International 2021).

Economic and environmental policies must be consistent at all levels (see box 2.13), alongside social protection and active labour market policies. This will ensure that the emerging green sectors foster formal, productive and decent employment, and it will reduce poverty and inequalities, particularly in developing countries.

Employment services, lifelong learning programmes, public employment schemes, entrepreneurship incentives, and job or wage subsidies are examples of activation measures that complement unemployment benefits and other social protection interventions to effectively support transition to sustainable economies (ILO 2017a). Such integration fosters fair, inclusive and socially just structural changes in production and consumption patterns, while securing public acceptance of environmental policies (ILO 2015c; 2017a; Pignatti and Van Belle 2018). Social protection measures, especially when complemented by activation programmes, mitigate job and income losses associated with phasing out polluting industries. This stabilizes consumption (ITUC 2018)6 and minimizes the ripple effects of environmental protection measures on communities and local businesses (Malerba 2022). By ensuring income security and business productivity and continuity, social protection measures enable workers and enterprises to smoothly navigate structural transformations. They manage the risks of adapting production models and taking up new jobs, thus preventing negative coping strategies such as terminating employees, accepting low-quality jobs, and child labour (Bischler et al. forthcoming; Peyron Bista and Carter 2017).

Box 2.13 Structural transformations in the context of a just transition

|

Historically, structural transformations towards higher-productivity and value-added economic sectors coincided with increased GDP, consumption and greenhouse gas emissions. Yet, today, governments are called to plan and establish pro-employment macroeconomic frameworks and integrated employment, social protection and industrial policies supporting structural transformation for climate action (2023q).

Many least developed countries face dilemmas due to reliance on economic activities based on natural resources. Achieving environmentally sustainable economies in these countries requires fair international trade policies and global value chains, cooperation in technology transfers, and the combating of illicit financial flows, notably in the mineral sector. Amid an urgent transition to sustainable production, some middle-income countries risk the “middle-income trap”, which is associated with insufficient productivity levels and limited structural transformation opportunities within a highly competitive global market. |

Sources: ILO (2015c; 2023q; 2022l; 2022j), UNCTAD (2022), Scheja and Kim (forthcoming), Bischler et al. (forthcoming) and Rodrik (2017).

Investing in human capabilities and facilitating transition to decent jobs in environmentally sustainable economies

Despite a net job gain in the medium term, mitigation and environmental protection policies will adversely affect employment and earnings due to changing skills demands. Such policies will particularly impact lower-skilled workers and those in the informal economy, who lack human and physical capital and social protection that can facilitate their transition to new jobs (Dercon 2014; Montt, Fraga and Harsdorff 2018; Klenert et al. 2018; ILO 2024k). Male-dominated sectors such as transport, energy, agriculture and construction, receive more attention in just transition discussions than female-dominated sectors such as textile and garments, despite the latter contributing to 6–8 per cent of total greenhouse gas emissions (Sharpe, Dominish and Martinez-Fernandez 2022; UN Women and UNIDO 2023). Prioritizing equal access to job placement, skills programmes, social protection, and developing the care sector, are crucial for ensuring women’s participation in green jobs (ILO 2019c; 2024a).

Linking social protection with active labour market policies can cushion the adverse impacts of climate policies on employment while enabling a transition to environmentally sustainable economies (ILO 2023f; 2023y; UN Women and UNIDO 2023) (see section 4.2.6). For instance, linking unemployment insurance with job placements and reskilling programmes has proven effective in supporting the energy transition (see box 2.14).

Thus, a just transition requires expanding social protection, including through tax-financed schemes, and strengthening active labour market policies to ensure inclusivity and formalization, especially for worker s in informal employment and new labour market entrants (Bischler et al. forthcoming; McKenzie 2017; Györi, Diekmann and Kühne 2021) (see section 3.2.2)

Modernizing and greening industries, such as waste management, requires government intervention, including social protection, to formalize and provide decent jobs for 20 million waste pickers globally. These workers are primarily women, children, older persons and migrants, who work with low pay and high exposure to hazardous products (WIEGO 2017; UN Women and UNIDO 2023).

Emerging green jobs, often linked to new technologies, offer opportunities for youth to transition from school into decent work. Equipped with necessary green skills and supported by social protection while seeking and starting employment, youth can act as catalysers of an environmentally sustainable future (ILO 2023y; 2024j). In addition, child benefits for young people over 18 years old can provide income security for young people while in education/training and help foster the formation of capabilities.

Ensuring coherence between employment, social protection and labour migration policies enables migrant workers to seize new and climate-resilient opportunities, and to actively contribute to the environmental transition, in a context of increasing labour shortage, including in natural resource-based sectors (ILO 2022g; 2024d; IMF 2018).

Protection of the environment requires an adjustment of agriculture, forestry and fishery production (ILO 2022b). For example, fishing restrictions call for the extension of social protection to fishers, by relaxing eligibility criteria for unemployment benefits (China7) or expanding in-kind social protection (Bangladesh) during fishing bans, providing temporary public employment (Mexico and South Africa) or combining non-contributory benefits with skills development measures for them to start small businesses, such as fruit and vegetable production (for example, Samoa and South Africa). Social protection measures, together with public employment or entrepreneurship programmes – complemented by agriculture and livestock insurance – help farmers to cope with the impact of climate policies on income, and to diversify their livelihoods and economic activities (FAO 2024). This enhances productive risk-taking in decisions related to agriculture production changes (Tirivayi, Knowles and Davis 2016; Jaspars, O’Callaghan and Stites 2008; Machado and Goode 2022).

Box 2.14 Linking social protection and active labour market policies for a just transition

|

In 2018, as part of the decision to phase out coal mining, the Government of Spain and the trade unions agreed on early retirement for miners who were over 48 years of age and those who had paid social security contributions for 25 years, as well as the local re-employment of miners in environment restoration work and their reskilling for the green industry, while receiving unemployment benefits. The Philippines’ Social Security System and Technical Education and Skills Development Authority collaborate to conduct job orientation, including in the circular economy, and to promote the social insurance registration of workers enrolled in the programmes run by the Technical Education and Skills Development Authority. To cope with both a severe drought in 2011 and a decline in international coffee prices, the Red de Protección Social (Social Protection Network) scheme of Nicaragua provided cash benefits to secure the income of small coffee producers and counselling services to diversify their agricultural activities. |

Sources: Furnaro et al. (2021); ILO (2017a); Maluccio and Flores (2005); WRI (2021b).

Supporting small enterprises and livelihoods

Mitigation and environmental protection policies can disrupt local economies and enterprises, especially micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (accounting for over 90 per cent of businesses) that are major job creators in developing countries (UNEP 2021; ILO 2019d; 2022e; 2023y). Adapting production models to comply with environmental regulations represents significant risks and costs for micro, small and medium-sized enterprises, especially given the limited technology and research and development in such countries (Ulrichs et al. 2019; Machado and Goode 2022; Davies, Oswald and Mitchell 2009). Social protection systems, which pool risks through collective financing, offer a cost-effective mechanism to support enterprises in navigating the green transition. For instance, providing access to a simplified social protection and tax regime for micro, small and medium-sized enterprises can support formalization, improve access to finance for technology investments, and enhance their economic resilience to transformations (Gaarder et al. 2021). Tripartite efforts in several countries (for example, Cambodia, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Nepal, Sao Tome and Principe, and Zambia) included the extension of social security to informal economy workers, as part of broader strategies to promote the transition of micro, small and medium-sized enterprises to environmentally sustainable activities (ILO 2013a; 2014a; 2015b; 2018b; 2019b; 2021l; 2021n).

By collectively financing risks and linking with broader policy framework, social protection enables micro, small and medium-sized enterprises to enhance productive risk-taking behaviour and competitiveness (World Bank 2003; ILO 2021i). This approach is central for improving workers’ resilience and ensuring business continuity and sustainable growth when facing challenges related to just transition efforts.

Box 2.15 The role of social dialogue in mitigation policies

|

Social partners in consultation with relevant stakeholders have played a crucial role in the coal transition. In Germany, the Coal Commission, which was established in 2018 by the Government, together with industry and trade unions representatives, to facilitate the coal phase-out by 2038, negotiated an agreement that protected workers through retraining and early retirement by means of a special adjustment fund. Workers’ rights and compensations were detailed in a contract between the State and coal plant operators, and early retirement was later enshrined in the law. |

Source: Furnaro et al. (2021).

The role of social dialogue

Tripartism and social dialogue are indispensable for designing and implementing social protection systems that address climate change challenges and the adverse impacts of mitigation efforts (see box 2.15). Collective bargaining, facilitated by bipartite and tripartite social dialogue, help craft national agreements to manage decarbonization impacts.

Social dialogue is essential for a just transition. In South Africa, the framework of the tripartite National Economic Development and Labour Council emphasizes the need for comprehensive social security reform for a just transition of the largest state-owned electric public utility (Nedlac 2020). In Colombia, the National Association of Entrepreneurs facilitated discussions on energy and mining transition among industry leaders, trade unions developed strategies for ensuring fair energy access, and the Government committed to a Green Jobs Pledge to support workers and employers with regard to green growth and a just transition, through social dialogue inclusive of indigenous peoples (Government of Colombia 2019).

2.2.3 Directly contributing to climate change mitigation and environmental protection

Mitigating the climate crisis ultimately requires major changes to production, energy use and consumption patterns. While the onus for change rests in other policy areas, there are ways that social protection can contribute to mitigation efforts, especially when it comes to pension fund investments and interventions to protect and restore ecosystems. In fact, all social protection institutional operations can be greened further (ISSA 2023b). For instance, institutions running health and social care schemes can use their purchasing power in procurement to support the greening of those services (ILO 2024f).

Accelerating the (green) transition through pension fund greening

As counterintuitive as it might sound, the fact parts of social protection have been, and continue to be, a major contributor to global heating is inconvenient. Pension funds (both private and public) with large-scale investments in the fossil fuel industry contribute to greenhouse gas emissions.8 While the returns from these investments have long financed old-age income security, they have left the children and grandchildren of their recipients facing a perilous future and inheriting a severely compromised planet.

Too little attention has been given to the opportunity of pension fund greening, which can also have considerable potential for influencing how global capital shapes the destiny of our planet (see section 4.3.1). The scale of pension assets cannot be ignored. They amount to US$53 trillion in the OECD alone (OECD 2023), representing a large tranche of the global capital market which was estimated at US$231 trillion at the end of 2022 for fixed income securities and equities (SIFMA 2023). Public pensions alone accounted for around US$22 trillion in 2021 (UNCTAD 2023), approximately 10 per cent of global capital. Pension assets are one of the largest singular blocks of capital in the world, can support the wider “imperative of definancialization” (Standing 2023) and can diminish the viability of fossil fuels. How these funds are invested can reconfigure and potentially transform socio-economic arrangements for greater sustainability, by shifting investments from the fossil fuel industry to the emerging green and renewables sector, thereby contributing to a transition away from fossil fuels and to the accelerated implementation of climate change mitigation.

Today, public pension funds are greening and implementing “environmental, social and governance” practices, as illustrated by the investment activity of the national public pension funds of Canada and Denmark. Both institutions have divested from emission-contributing companies and invested in green fund portfolios (UNCTAD 2023, see boxes 4 and 5). There are also subnational examples. The New York City Pension Funds have been steadily divesting from fossil fuels since 2015 and have increasingly invested in climate solutions (such as renewable energy, energy efficiency, pollution prevention and low-carbon buildings). In 2021, the Funds committed to achieving net zero by 2040 and established safeguards against any greenwashing risks (New York City 2023).

More effort in divestment and greening public pension funds is surely overdue. Both self-interest (reliable return on investment as evidenced in section 4.3.9) and altruism (a viable planet for future generations) can be dual motivations for workers’ and employers’ organizations and civil society organizations to mobilize to ensure these funds support mitigation and ensure fossil fuel– free old-age income security. Moreover, given that these funds are mainly nestled in wealthier countries, from a North–South equity perspective with greater recognition of how the investment of these funds adversely affect billions of people – often on the front line of the climate crisis and lacking access to social protection – should be a basic human concern.

Supporting the preservation and restoration of carbon sinks and natural resources through social protection

Payment for ecosystem services, conditional cash transfer schemes and public employment programmes can be designed to simultaneously fulfill social protection (i.e., providing income security) and environmental objectives (ILO, UNEP, and IUCN 2022). For example, the Proyecto Pobreza, Reforestación, Energía y Cambio Climático (Poverty, Reforestation, Energy and Climate Change Project)9 in Paraguay links the basic Tekoporã10 conditional cash transfer to additional payments if the recipients achieve positive agroforestry production outcomes. This is expected to not only increase agricultural productivity and incomes, but also protect forests, which act as important carbon sinks (Györi, Diekmann and Kühne 2021).

Such initiatives can also benefit from traditional knowledge of indigenous communities on environmental use and protection (Errico 2018; Cooke et al. 2017). In Brazil, a conditional cash transfer incentivizes owners and users of natural resources (for example, forests or water) to conserve or use them in a sustainable manner. Between 2011 and 2016 the Bolsa Verde programme provided additional benefits to 31,621 participants of the Bolsa Família programme in the Amazon region, and was conditional on their non-participation in environmentally harmful activities such as illegal logging (Schwarzer, van Panhuys and Diekmann 2016; McCoshan 2020). Analyses indicate that, thanks to the programme, deforestation was 22 per cent lower compared to other areas (Wong et al. 2024), and substantial carbon reduction benefits were created (McCoshan 2020), contributing to the protection of the Amazon, which is a major global carbon sink. The programme was reinstated in 2023 with a renewed focus on combining poverty reduction and sustainable resource use objectives.11

Furthermore, public employment programmes also increasingly focus on environmental asset creation and protection, such as Ethiopia’s Productive Safety Net Programme, which was shown to contribute to carbon sequestration by building soil organic carbon and increasing biomass (Tefera et al. 2015). Particular attention needs to be paid in designing and implementing public employment programmes to ensure decent work, gender-responsiveness and respect for human and labour rights (Ravallion 2016; Sengupta 2019; Razavi et al., forthcoming a; McCord et al., forthcoming).

In some contexts, social protection, even without explicit environmental objectives, can also lead to greener results. Income support can reduce the need to engage in unsustainable practices, such as deforestation, and enable people to consume market-sourced goods rather than directly tapping into natural resources. For example, Indonesia’s Keluarga Harapan social assistance programme was found to reduce forest cover loss by between 16 and 30 per cent. (Ferraro and Simorangkir 2020).

While conditionality in social protection is not without problems (Cookson 2018; Orton 2014), such schemes can have a positive impact on afforestation rates and reducing ecologically harmful activities. However, they need to go to scale, as some have already, in order to achieve a widespread and sustainable positive impact (Schwarzer, van Panhuys and Diekmann 2016). At the same time, care must be taken to address structural inequalities that are the principal drivers of ecological damage, such as consumption patterns, luxurious lifestyles and polluting industries (ISSA 2014, see box 2.8). This means directly addressing structural inequalities that are the root cause of the crisis and not shifting the onus of environmental conservation onto communities who have least contributed to it and who are already vulnerable themselves.

Figure 2.3a The state of social protection worldwide: Coverage is increasing but too slowly

Note: Due to rounding, some totals may not correspond to the sum of the separate figures.

Sources: ILO estimates, World Social Protection Database, based on the Social Security Inquiry; ISSA Social Security Programs Throughout the World; ILOSTAT; WHO; national sources.

1 This rate refers to effective coverage for children aged 0 to 15. The rate for children aged 0 to 18 is lower at 23.9 per cent.

Figure 2.3b The 20 and 50 countries most vulnerable to climate change and their weighted average effective coverage by at least one social protection cash benefit, 2023

Disclaimer: Boundaries shown do not imply endorsement or acceptance by the ILO. See full ILO disclaimer.

Notes: See Annex 2 for a methodological explanation. Global and regional aggregates are weighted by population group.

Sources: ILO estimates, World Social Protection Database, based on the Social Security Inquiry; ISSA Social Security Programs Throughout the World; ILOSTAT; national sources and Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative Country Index.